Superman, Destroyed Bodies, and All Our Tomorrows

When the Ku Klux Klan was trying to recruit new members in post-World War II United States, the Anti-Defamation League reached out to the producers of the massively popular Superman radio show and proposed a story that pitted the organization as villains against the Man of Steel. The 16-part series “The Clan of the Fiery Cross” was a ratings hit and seriously damaged the Klan’s recruitment efforts and membership numbers. The way this superhero radio serial dealt a blow to hatred is an awesome example of why stories are so powerful.

Last year, MacArthur Foundation Fellow Gene Luen Yang and the artist cohort Gurihiru adapted this 1946 radio story into the graphic novel Superman Smashes the Klan. My parents shipped it to me last week as a birthday present and I loved it. The only way this mixture of superheroes, justice issues, and American history could be more in my wheelhouse is if it featured a lengthy scene in which Superman and Jimmy Olsen discussed theology.

The graphic novel has not been far from my mind since I finished it. The story is beautiful, fun, and well-told. Yet its continued presence in my mind is due to recent events demonstrating how little the world has changed since 1946. Maybe the violence is not committed by men in white hoods who burn crosses, but violence against those who are not white still persists.

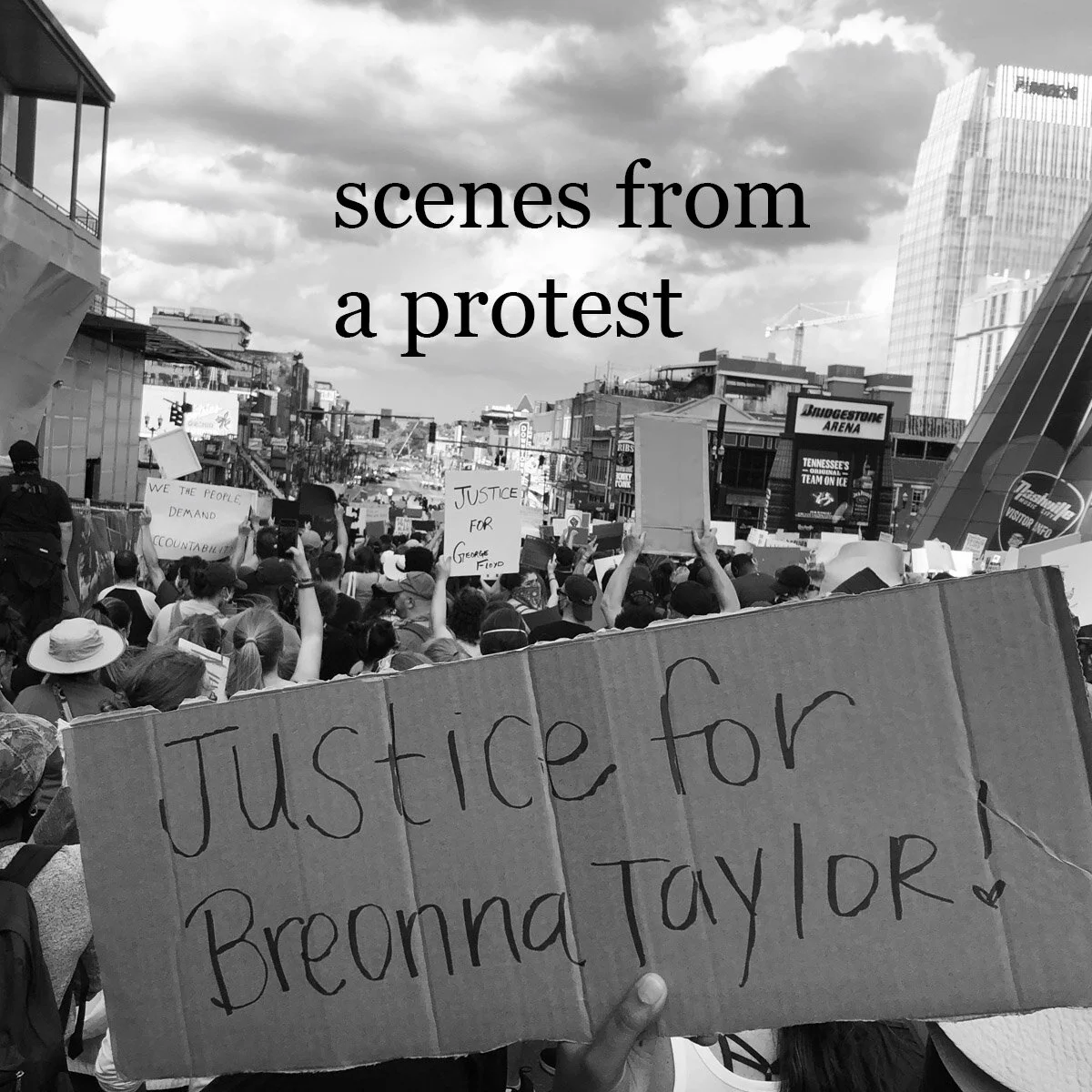

Back in February, Ahmaud Arbery was murdered by self-appointed vigilantes while jogging in a neighborhood. It wasn’t until a viral video caught the attention of the nation months later that the men were actually arrested. Yesterday, a police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck as he cried out that he could not breathe. A gathering crowd begged the officer to stop. For at least five minutes of video the officer pressed the neck of a distraught and struggling man to asphalt. Mr. Floyd died later in the hospital.

Mr. Floyd’s cries of being unable to breathe call to mind the cries of Eric Garner. While arresting him, officers put Mr. Garner in a chokehold and the man repeatedly declared that he could not breathe. He would die later that day in a hospital.

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son, “It is not necessary that you believe that the officer who choked Eric Garner set out that day to destroy a body. All you need to understand is that the officer carries with him the power of the American state and the weight of an American legacy, and they necessitate that of the bodies destroyed every year, some wild and disproportionate number of them will be black.”

That is the reality with which white citizens of this country have to contend. Racism is not just hoods and burning crosses. It is not just people flying the Stars and Bars who use the n-word. It is a system that is baked into this country. It’s a system that makes the statement “Black Lives Matter” controversial. We can’t assume that this system is someone else’s problem.

One of the characters in Superman Smashes the Klan is a kid named Chuck Riggs. When we meet Chuck, he hurls racial slurs at Roberta and Tommy Lee, the Chinese-American protagonists of the story. We later discover that his uncle is the leader of the local chapter of the Klan who decides to make an example of the Lees. When their cross-burning intimidation does not scare the Lees back to Chinatown and The Daily Planet begins to offer rewards to anyone who can provide information that will stop the Klan, the elder Riggs decides to take his hatred further by kidnapping Tommy (who breaks his arm in a successful escape) and then bombing Unity House, an ecumenical community center.

Chuck begins to come around. Yet despite seeing the evil that exists in his uncle’s actions, the kid still struggles with fully fighting against the Klan’s terrorism:

Chuck: Hey Tommy? I’ve been thinking…what happened to the Unity House was absolutely wrong, of course. But…is it really all that bad to want to live around only people who look like you?

Tommy; What are you saying, Chuck?

Chuck: I…I don’t know! I’m just trying to make sense of it all!

Tommy: A broken arm’s not enough? You want me to quit the team?!

Chuck: No, no! That’s not…

Tommy: You want my family to move back to Chinatown, is that it?!

Chuck: I…I…!

Tommy: Spit it out!

Chuck: I want to know that my family’s not evil!

I wonder sometimes if our slowness as white people to join our brothers and sisters of other ethnicities in battling racial injustice is that we simply don’t want to believe that the evil runs that deep or that being white provides so much greater an advantage in this country. We have to admit that we benefit from this broken system. We don’t want the evil to be part of our legacy, but it is whether we like it or not. We want to know that our American family is not that evil.

Yet that evil persists and inflicts harms on our brothers and sisters. As a Christian (which admittedly is quite a different thing than being an American), I hold to the Apostle Paul’s assertion that in Christ we are one regardless of race, gender, station in life, etc. They are all part of our family. What happens to one of us matters to all of us. We are intertwined with one another.

In the final pages of the graphic novel, Superman holds Chuck’s uncle aloft over the city of Metropolis after thwarting a bombing with the help of Roberta. Ever the paragon of hope, the Man of Tomorrow tries to get Riggs to understand our interconnectedness: “But we are bound together. The Lees and I…our friends at the Daily Planet and the Unity House and the police department…everyone down there, really…we are bound together by the future. We all share the same tomorrow. That includes even you, once you’ve renounced your hate and paid for what you’ve done….There’s always a tomorrow.”

We all share tomorrow. We must listen and learn and reckon with evil and act in whatever way we can for all of our tomorrows. Too many of our sisters and brothers have been robbed of their tomorrows. As much as we would like us to, we do not have Superman to smash the hatred around us. We cannot wait for someone else. It’s on us. We are bound together. Let us never forget that.